Chapter 7. Objects and Operator-Pending Mode

The navigation and motion commands we’ve learned so far are invaluable, but Neovim also comes with several more advanced motions that can supercharge your editing workflow. LazyVim further amends this collection of motions with other powerful navigation capabilities powered by a variety of plugins.

For example, if you are editing text rather than source code, you will find it

useful to be able to navigate by sentences and paragraphs. A sentence is

basically anything that ends with a ., ?, or ! followed by whitespace.

The sentence keybindings are two of the hardest for me to remember. I use them rarely enough that it hasn’t become muscle memory, and it doesn’t have a good mnemonic I can remember.

Have I built enough suspense? Pay attention, because you will forget this. To

move one sentence forward (to the first letter after the whitespace following

sentence ending punctuation), type a ) (right parenthesis) command in normal

mode. To move to the start of the current sentence, use (. Press the

parenthesis again to move to the next or previous sentence or a add count if

you want to move by multiple sentences.

I hate that the command is ( since that feels like it should be moving to,

you know, a parenthesis! But it’s not; it’s moving by sentences. Since the .,

!, and ? characters rarely mean “sentence” in normal software development,

I just don’t use it that much until I start writing a book (something I keep

telling myself I won’t commit to again, but it never lasts).

| In addition to stopping after punctuation followed by whitespace, navigating by sentence also stops on "paragraph boundaries", which is to say "blank lines". If you are using sentences with counts, this can throw your navigation off because you need to add an extra step for each paragraph, as well as the punctuation that normally defines a sentence. |

I do use the paragraph motions all the time, though. A paragraph is defined as

all the content between two empty lines, and that is a concept that makes sense

in a programming context. Most developers structure their code with logically

connected statements separated by blanks. The commands to move up or down by

one “paragraph” are the curly braces, { and }. If you need to jump

multiple paragraphs ahead or back, they can, as usual, be prefixed by a count.

Again, you might expect { to jump to a curly bracket, so it is a bit annoying

that it means “empty line” instead, but once you get used to it, you’ll probably

reach for it a lot.

7.1. Unimpaired Mode

LazyVim provides a bunch of other motions that can be accessed using square

brackets. It will take a while to internalize them all, but luckily, you can

get a menu by pressing a single [ or ]. Like the sentence and paragraph

motions, the square brackets allow you to move to the previous or next

something, except the something depends what key you type after the

square bracket.

Collectively, these pairs of navigation techniques are sometimes referred to as “Unimpaired mode”, as they harken back to a foundational Vim plugin called vim-unimpaired by a famous Vim plugin author named Tim Pope. LazyVim doesn’t use this plugin directly, but the spirit of the plugin lives on.

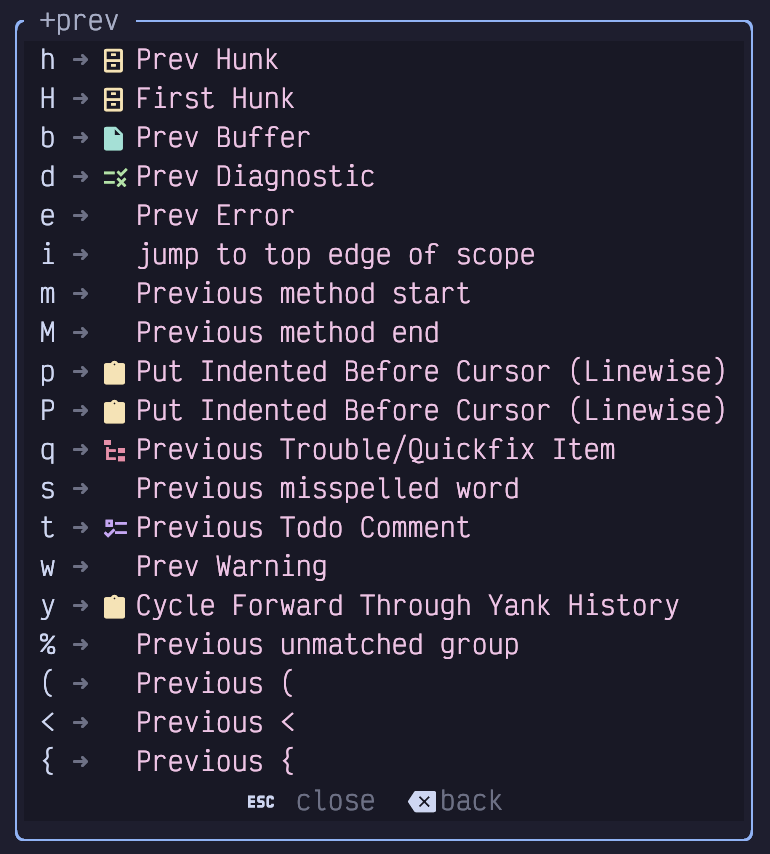

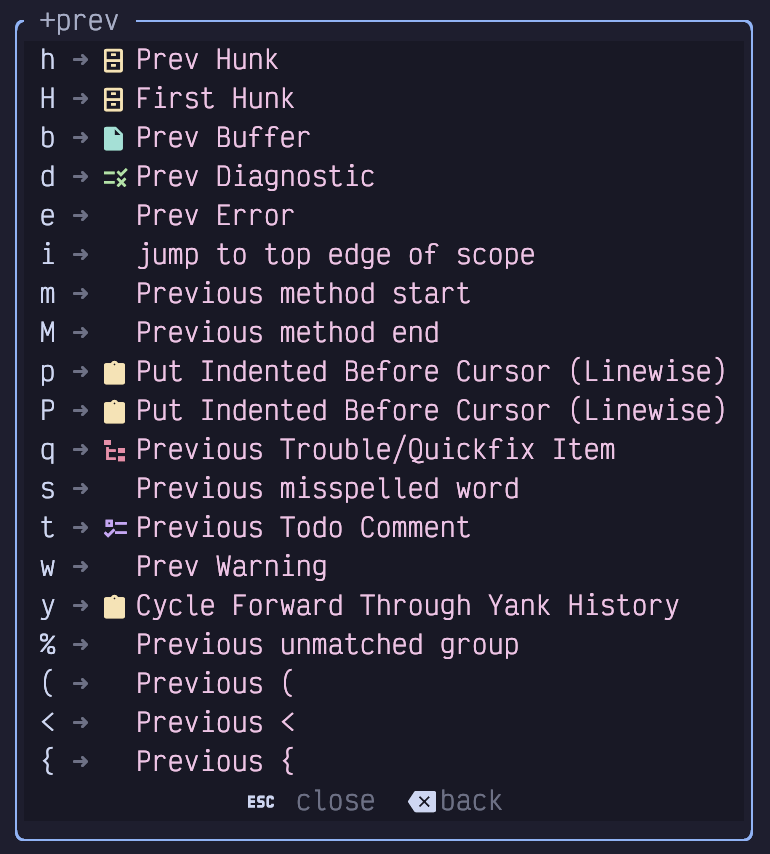

Here’s what I see if I type [ and then pause for the menu:

Figure 25. Unimpaired Mode Menu

Not all of these are related to navigation, and one of them is only there because I have a Lazy Extra enabled for it. We’ll cover the motion related ones here and most of the others in later chapters.

First, the commands to work with (, <, and { are quite a bit more nuanced

than they look. They don’t blindly jump to the next (if you started

with ]) or previous (if you used [) parenthesis, angle bracket, or curly

bracket. If you wanted to do that, you could just use f( or F(.

Instead, they will jump to the next unmatched parenthesis, angle bracket, or

curly bracket. That effectively means that keystrokes such as [( or ]} mean

“jump out”. So if you are in the middle of a block of code surrounded by {}

you can easily jump to the end of that block using ]} or to the beginning of

it using [{, no matter how many other curly-bracket delimited code blocks

exist inside that object. This is useful in a wide variety of programming

contexts, so invest some time to get used to it.

As a shortcut, you can also use [% and ]% where the % key is basically a

placeholder for “whatever is bracketing me.” They will jump to the beginning or

end of whichever parenthesis, curly bracket, angle bracket, or square bracket

you are currently in.

That last one (square bracket), is important, because unlike the others, [[

and ]] do not jump out of square brackets, so using [% and ]% is your

only option if you need to jump out of them.

7.1.1. Jump by Reference

Instead of jumping out of square brackets as you might expect, the easy to

type [[ and ]] are reserved for a more common operation: jumping to other

references to the variable under the cursor (in the same file).

This feature typically uses the language server for the current language, so it is usually smarter than a blind search. Only actual uses of that function or variable are jumped to instead of instances of that word in the middle of other variables, types, or comments as would happen with a search operation.

As you move your cursor, LazyVim will automatically highlight other variable

instances in the file so you can easily see where ]] or [[ will move the

cursor to.

7.1.2. Jump by Language Features

The [c, ]c, [f, ]f, [m, and ]m keybindings allow you to navigate

around a source code file by jumping to the previous or next class/type

definition, function definition, or method definition. The usefulness of these

features depends a bit on both the language you are using and the way the

Language Service for the language is configured, but it works well in common

languages.

By default, those keybindings all jump to the start of the previous or next

class/function/method. If you instead want to jump to the end, just add a

Shift keypress: [C, ]C, [F, ]F, [M, and ]M will get you there.

Note that these are not the same as “jump out” behaviour: if you have a

nested or anonymous function or callback defined inside the function you are

currently editing, the ]F keybinding will jump to the end of the nested function,

not to the end of the function after the one you are currently in.

I personally don’t use these keybindings very much as there are other ways to

navigate symbols in a document that we will discuss later. But if you are

editing a large function and you want to quickly jump to the next function in

the file, ]f is probably going to get you there faster than using j with a

count you need to calculate, or even a Control-d followed by S to go to seek

mode.

7.1.3. Jump to End of Indention

If you are working with indentation-based code such as Python or deeply nested

tag-based markup such as HTML and JSX, you may find the [i and ]i pairs helpful.

These are provided as part of the snacks suite of plugins, via

snacks.indent. This plugin helps visualize the levels of indentation in a

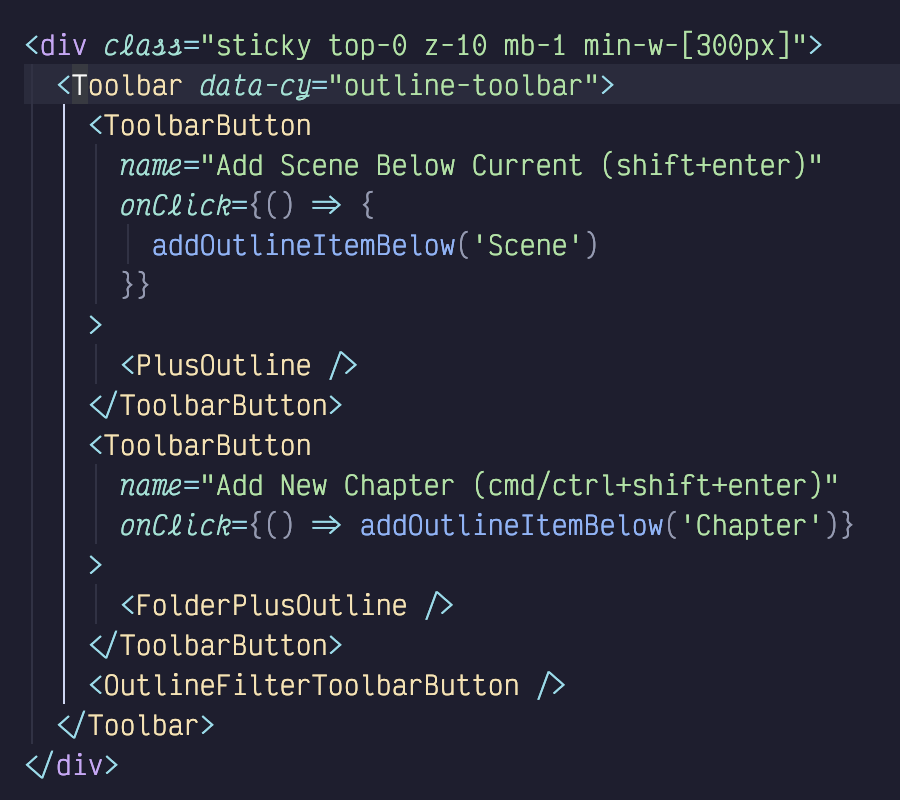

file. Here’s an example from a Svelte component I was working on recently:

Figure 26. Indent Guides

This Svelte code uses two spaces for indentation. Each level of indentation has a (in my theme) grey vertical line to help visualize where that indentation level begins and ends, and the “current” indentation level is highlighted in a different colour.

In addition, the plugin adds the unimpaired commands [i or ]i to jump out

of the current indentation level; it will go either to the top or the bottom of

whichever indentation line is currently highlighted.

I use this functionality all the time when editing Python code and Svelte

components. I use it less often in other languages where [% and ]% tend to

get me closer to where I need to go next. But the visual feedback of indent

guides can be super helpful, even in bracket-heavy languages; I may be surprised

by which curly bracket I will “jump out” to, but the indent guides are always

obvious.

7.1.4. Jumping to Diagnostics

I don’t know about you, but when I write code, I tend to introduce a lot of errors in it. Depending on the language, LazyVim is either preconfigured or can be configured to give me plenty of feedback about those errors, usually in the form of a squiggly underline

| If you aren’t seeing squiggly underlines, go back to Chapter 1 and pick a better terminal. |

These squiggly underlines are usually created by integration with compilers, type checkers, linters, and even spell checkers, depending on the language. Some of them are errors, some are warnings, some are hints. Some are just distractions, but most of them are opportunities to improve your code.

Because I am so incredibly talented at introducing problems in my code, a

common navigation task I need to perform is “jump to the next squiggly line”.

Collectively, these are referred to as diagnostics, so the key combinations

are [d and ]d. If you only want to focus on errors and ignore hints and

warnings, you can use [e and ]e. Analogously, the [w and ]w keybindings

navigate between only warnings.

If you are editing a file in a language that enables spellcheck, or you have

enabled it explicitly with <Space>us, misspellings can be jumped to with [s and

]s. This tripped me up when I started this book because I expected the ]d

to take me to the squiggly underlines under misspelled words, but it doesn’t. I

need ]s instead.

Finally, if you use TODO or FIXME comments in your code, you can jump

between them using [t and ]t.

Note that unlike most of the previous ] and [ keybindings, it is not

possible to combine diagnostic jumps with a verb. So d[d will not delete

from the current location to the nearest diagnostic. This is (probably)

just an oversight in how LazyVim defines the keybindings.

7.1.5. Jumping to Git Revisions

This is actually my favourite of the square bracket pairs: [h and ]h allow

you to jump to the next git “hunk”. If you aren’t familiar with the word (or if

you’re from a generation that thinks it means a gorgeous man), a “git hunk” just

refers to a section of a file that contains modifications that haven’t been

staged or committed yet.

A lot of my editing work involves editing a large file in just three or four

places. For example, I might add an import at the top of the file, an argument to

a function call somewhere else in the file, and change the function that

receives that argument in a third place. Once I’ve started editing, I may have

to jump back and forth between those locations. ]h and [h are perfect for

this, and I don’t need to remember my jump history or add named marks

(essentially bookmarks) to do it.

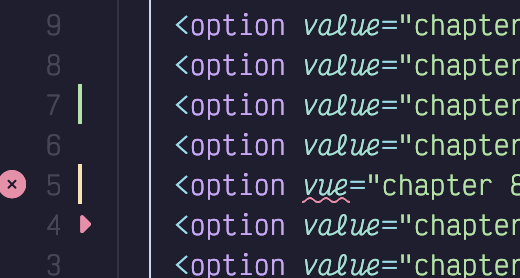

Even better, LazyVim gives you a simple visual indicator as to which lines in the file have been modified, so you have an idea where it’s going to jump. Have a look at this screenshot:

Figure 27. Git Hunk Indicators

On the left side, to the right of the line numbers, you can see a green

vertical bar where I inserted two lines, an orange bar where I changed a line,

and a small red arrow indicating that I deleted a line. (As a bonus, it also

shows a diagnostic squiggly and a red x-in-circle to the left of the line

numbers on the line where my modification introduced the error). If I place my

cursor at the top of the file and type ]h three times, I will jump between

those three places.

Like diagnostics, [h and ]h cannot be combined with a verb.

7.2. Text Objects

Combining verbs with motions is very useful, but it is often more helpful to combine those same verbs with objects instead of motions. Vim comes with several common objects, such as words, sentences and the contents of parenthesis. LazyVim adds a ridiculous pile of other text objects.

The grammar for objects is <verb><context><object>. The verbs are the same

verbs you have already learned for working with motions, so they can be d,

c, gU, etc.

The context is always either a or i. As you know, these are two commands to

enter Insert mode from Normal mode. But if you have already typed a verb such

as d or c, you are technically not in Normal mode anymore!

You are in the so-called “Operator Pending Mode”. The navigation keystrokes you are familiar with are generally also allowed in Operator-Pending mode, which is the real reason you can perform a motion after a verb. But if a plugin maintainer neglects to define the operator-pending keymaps, you end up with situations where you can navigate but not perform a verb.

It doesn’t make sense to switch to Insert mode after an operator, so the a

and i keystrokes mean completely different things. Typically, you can think

of them as around and inside (though in my head I always just pronounce

them as “a” and “in”). The difference is that a operations tend to select

everything that inside selects plus a bit of surrounding context that

depends on the object that is defined.

For example, one common object is the parenthesis: (. If you type the command

di(, you will delete all the text inside a matched pair of parenthesis.

But if you instead type da(, you will delete all the text inside the parenthesis

as well as the ( and ) at each end.

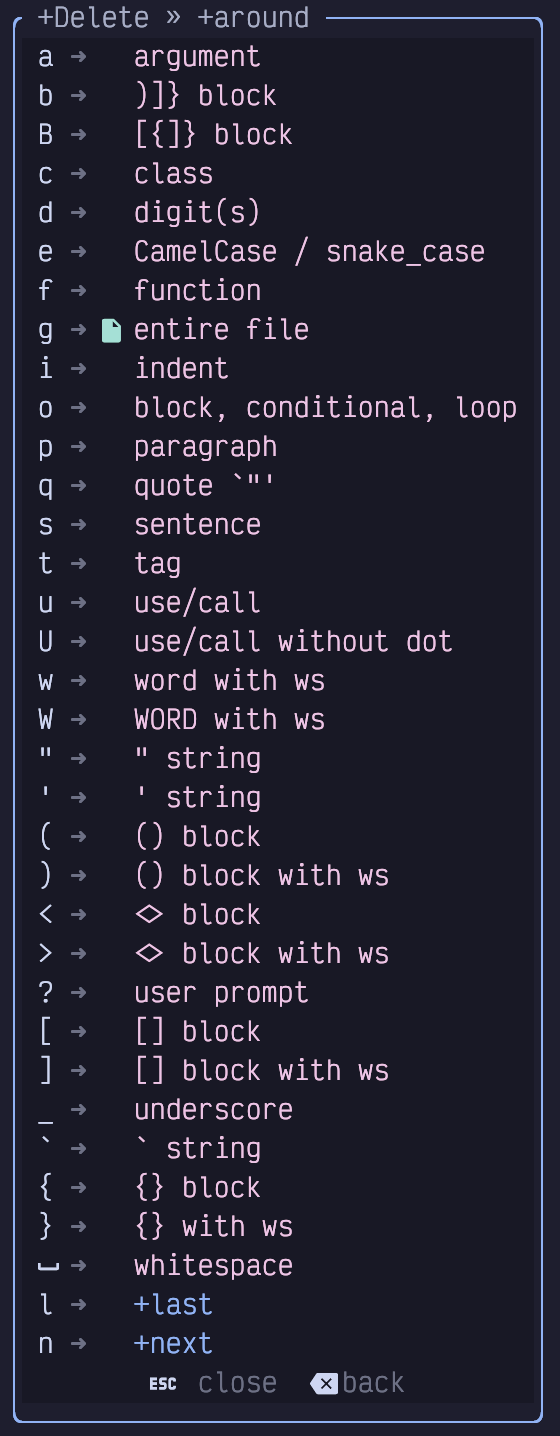

To see a list of many possible text objects in LazyVim, type da and pause. Here’s

what I see:

Figure 28. Operator Pending Menu

Let’s cover most of these in detail next.

7.2.1. Textual Objects

The operators w, s, and p are used to perform an operation on an entire

word, sentence, or paragraph, as defined previously: word is contiguous

non-punctuation, sentence is anything that ends in a ., ?, or !, and

paragraph is anything separated by two newlines.

The difference between around and inside contexts with these objects

is whether or not the surrounding whitespace is also affected.

For example, consider the following snippet of text and imagine my cursor

is currently at the | character in the middle of the word handful in

the second sentence:

Listing 18. A Plain Text Paragraph

This snippet contains a bunch of words. There are a hand|ful of

sentences.

And two paragraphs.If I want to delete the word handful while I’m at that location, I could type

bde to jump to the back of the word, then delete to the end of the word.

Or I can use the inside word text object and type diw.

Either way, I end up with an extra space between a and of because diw is

inside the word and doesn’t touch surrounding whitespace.

If I instead type daw, it will delete the word and one surrounding space

character, so everything lines up correctly afterward with a single space

between a and of.

There is also a W (capitalized) operator that has a similar meaning to the

captial W when navigating by words: it will delete everything between two

whitespaces instead of interpreting punctuation as a word boundary.

Similarly, I can use dis and das from that same cursor position to delete

the entire “There are a handful of sentences.” sentence. The former won’t touch

any of the whitespace before The or after the ., while the latter will sync

up the whitespace correctly.

Finally, I can delete the entire paragraph with dip or dap. The difference

is that in the former case, the blank line after the paragraph being deleted

will still be there, but in around mode, it will remove the extra blank.

Typically, I use i when I am changing a word, sentence or paragraph, with a

c verb, since I want to replace it with something else that will need to have

surrounding whitespace. But I use a when I am deleting the textual object

with d because I don’t intend to replace it, so I want the whitespace to

behave as if that object never existed.

7.2.2. Quotes and Brackets

The objects ", ', and ` operate on a string of text surrounded with

double quotes, single quotes, or backticks. If you use the command ci", you

will end up with your cursor in Insert mode between two quotation marks, where

everything inside the string was removed. If you use da", however, it will

delete the quotation marks as well.

As a shortcut, you can use the letter q as a text object and LazyVim will

figure out what the nearest quotation mark is, whether single, double, or

backtick, and delete that object. I don’t use this, personally, but I guess it

would save a keypress on double quotes.

Similarly if you want to apply a verb to an entire block contained in

parentheses or curly, angle, or square brackets, you just have to type one of

those bracketing characters. Consider, these examples: di[, da(, ci{ or

ca<. As with quotes, the i versions will leave the surrounding brackets

intact, and the a version will delete the whole thing.

The shortcut to select whatever the nearest enclosing bracket or parenthesis

type is the b object. (Mnemonic is “bracket”).

These actually work with counts so you can delete the “third surrounding curly

brackets” instead of the “nearest surrounding curly brackets” if you want to. I

can never remember where to put the count, though! If your memory is better than

mine, the syntax is to place the count before the a or i. So for example,

d2a{ will delete everything inside the second-nearest set of curly brackets.

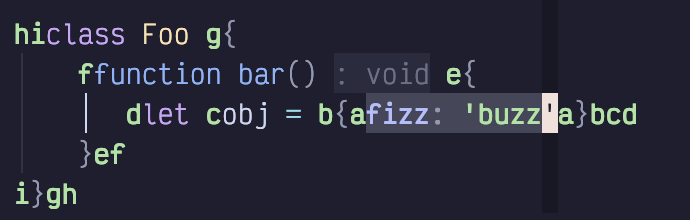

I’m not sure if that makes sense, so here’s a visual:

Listing 19. An Odd Little Class

class Foo {

function bar() {

let obj = {fizz: 'buzz'}

}

}If my cursor is on the colon between fizz and 'buzz' then you can expect

the following effects:

di{will deletefizz: 'buzz'but leave the surrounding curly brackets.c2i{will remove the entirelet obj =line and leave my cursor in Insert mode inside the curly brackets defining the function body.c2a{will do the same thing, but also remove those curly brackets, so I’m left with afunction bar()that has no body.d3i{will remove the entire function and leave me with an emptyFooclass.

You can also delete things between certain pieces of punctuation. For example,

ci* and ca_ are useful for replacing the contents of text marked as bold

or italic in Markdown files.

If you want to operate on the entire buffer, use the ag or ig text object.

So cag is the quickest way to scrap everything and start over and yig will

copy the buffer so you can paste it into a pastebin or chatbot. The g

may seem like an odd choice, but it has a symmetry to the fact that gg and

G jump to the beginning or end of the file. If you need a mnemonic,

think of yig as “yank in global”.

7.2.3. Language Features

LazyVim adds some helpful operators to perform a command on an entire function or class definition, objects, and (in HTML and JSX), tags. These are summarized below:

c: Act on class or typef: Act on function or methodoAct on an “object” (the mnemonic is a stretch) such as blocks, loops, or conditionalstAct on an HTML-like tag (works with JSX)iAct on a “scope”, which is essentially an indentation level (only available if the aforementioned mini.indentscope extra is installed)

7.2.4. Git Hunks

Remember the git hunks we discussed with Unimpaired mode? You can similarly act

on an entire hunk with the h object. So one way to quickly revert an addition

is to just type dih. But you probably won’t do this much as there are better

ways to deal with git, as we will discuss in Chapter 15.

7.2.5. Next and Last Text Object

The text object feature is great if you are already inside the object you want to operate on, but LazyVim is configured (using a plugin called mini.ai) so that you can even operate on objects that are only near your cursor position.

Once installed, the next and last text objects can be accessed by

prefixing the object you want to access with a l or n.

Consider the Foo.bar Javascript class again:

Listing 20. That Odd Class Again

class Foo {

function bar() {

let obj = {fizz: 'buzz'}

}

}If my cursor is on the { of the function bar line, I can type cin{ to delete

the contents of the fizz: 'buzz' object and place my cursor there in insert

mode. I can save myself an entire navigation with just one extra n keystroke.

I think this is a really neat feature, but I tend to forget it exists…

hopefully writing about it here will help me remember!

7.3. Seeking Surrounding Objects

The flash.nvim plugin that gave us Seek mode, has another trick up its

sleeve: the holy grail of text objects. After specifying a verb, you can use

the S key (there is no i or a required) to be presented with a bunch of

paired labels around the primary code objects surrounding your cursor.

As an example, I’m going to lean on that Foo class again. I have placed

my cursor on the : and typed cS. The plugin identifies the various objects

surrounding my cursor and places labels at both ends of each object:

Figure 29. Seek Surrounding Object

The labels in this image are in green, and (typically) go in alphabetical order

from “innermost” to “outermost”. The primary difference from Seek mode is that

each label comes in pairs; there are two a labels, two b labels, and so on.

The text object is whatever is between those labels.

If the next character I press is a (or enter, to accept the default), then I

will change everything inside the curly brackets defining the obj. If I press

b, it will also replace those curly brackets. Pressing c will change the

entire assignment and d will change the contents of the function. Hitting e

replaces the curly brackets as well, and f changes the full function

definition. The g label is the contents of the class, while h changes the

entire class.

This is a super useful tool when you need to change, delete, or copy a complex structure that does not immediately map to any of the other objects.

7.3.1. Seeking Surrounding Objects Remotely

The S Operator-pending mode is useful for acting on objects that surround the

cursor, but if your cursor isn’t currently within the object you want to

select, it won’t suffice. You could use s to navigate to inside the object

followed by S to select it, but you can save yourself a few keystrokes by

instead using the R operator.

With a mnemonic of “Remote”, R is easy to use, but hard to explain. It is

an operator-pending operation, so you need to type a verb first, followed by

R (as with S , there is no i or a required).

At this point, LazyVim is essentially in Seek mode, so you can type a few characters from a search string to find matches anywhere on the screen. However, instead of showing a single label at any matches for the string you searched for, flash.nvim will automatically switch to surrounding object mode, and show pairs of labels of all constructs that surround the matching locations.

To put the icing on the cake, you can also perform a remote seek on any kind of

object without using the surround mode. In this case, you would type a verb

followed by a lowercase r (it still means “remote”). This will also put

you in Seek mode, and you can start typing the matching characters. Single

(normal Seek mode, rather than Surround Seek mode) labels will pop up, and you

can enter a character to temporarily move your cursor to that label, just like

normal Seek mode. But when your cursor arrives there, it is automatically

placed in Operator-pending mode again. So you can now type any other operator

such as aw or i(. Once the operation completes, your cursor will move back

to where it was before you entered the remote Seek mode.

As a specific example, the command drAth2w will delete two words starting at

the word “At” that gets the label h, then jump your cursor back to the

position it was at before you started the delete. In other words, it is the

same as the command sAthd2w<Control-o>, which will seek to the word “At” at

label h, then delete two words, and use Control-o to jump back to your

previous history location. The remote command is a little shorter, but it’s

another one that I tend to forget to use. My brain goes into “move the cursor”

mode before it figures out “delete” mode, so by the time I realize I could have

done it remotely, it’s too late.

7.4. Operating on Surrounding Pairs

We’ve already seen the text objects to operate on the contents of pairs of quotation marks or brackets, but what if you want to keep the content but change the surrounding pair?

Maybe you want to change a double quoted string such as "hello world" to a

single quoted 'hello world'. Or maybe you are changing a

obj.get(some_variable) method lookup to a obj[some_variable] index lookup,

and need to change the surrounding parentheses to square brackets.

LazyVim ships with the mini.surround plugin for this kind of behaviour, but it’s not installed by default. It is a recommended extra, so if you followed my suggestion to enable all the recommended plugins, you may have it already.

7.4.1. Add Surrounding Pair

The default verb for adding a surrounding pair is gsa. That will place your

editor in operator-pending mode, and you now have to type the motion or text

object to cover the text you want to surround with something. Once you have

finished inputting that object, you need to type the character you want to

surround it with, such as " or ( or ). The difference between the latter

two is that, while both will surround the text with parentheses, the ( will

also put extra spaces inside the parentheses.

That may sound complicated, but it should make sense after you see some examples:

gsai[(will select the contents of a set of square brackets (usingi[) and place parentheses separated by spaces inside the square brackets. So if you start with[foo bar]and typegsai[(, you will end up with[( foo bar )].gsai[)does the same thing, except there are no spaces added, so the same[foo bar]will become[(foo bar)].gsaa[)will place the parentheses outside the square brackets, because you selected witha[instead ofi[. So this time, our example becomes([foo bar]).gsa$"will surround all the text between the current cursor position and the end of the line with double quotation marks.gsaSb'will surround the text object that you select with the labelbafter anSoperation with single quotation marks.gsaraa3e*will surround the remote object that starts withathat is labelled with anafollowed by the next three words with an asterisk at each end of the three words.

Depending on the context it can be a lot of characters to type, but it’s typically fewer characters than navigating to and changing each end of the pair independently.

7.4.2. Delete Surrounding Pair

Deleting a pair is a little easier, as you don’t need to specify a text object.

Just use gsd followed by the indicator of whichever pair you want to remove.

So if you want to delete the [] surrounding the cursor, you can use gsd[.

If you want to delete deeply nested elements, you need to put a count

before the gsd verb. So use 2gsd{ to delete the second set of curly braces

outside your current cursor position. For example, if your cursor is

inside the def of the string {abc {def}}, typing 2gsd{ results in abc

{def}, leaving the “inner” curly braces around def, but removing the second

outer set around the whole.

7.4.3. Replace Surrounding Pair

Replacing is similar to deleting, except the verb is gsr and you need to type

the character you want to replace the existing character with after you type

the existing character.

So if you have the text "hello world" and your cursor is inside it, you can use

gsr"' to change the double quotes to single quotes: 'hello world'.

7.4.4. Navigate Surrounding Characters

Performing operations on surrounding pairs or on the entire contents of the

pair is convenient, but sometimes you just want to move your cursor to the

beginning or end of the pair. You can often do this using Seek mode, Find mode,

or the Unimpaired mode commands such as [(, but there are other commands that

are more syntax aware if you need them.

The easiest one has been built into Vim for a long time. If your cursor is

currently on the beginning or ending character of a parenthesis, bracket, or

curly brace pair, just hit % to jump to its mate at the other end of the

parenthetical. If you use % in Normal mode when you aren’t on a pair, it will

jump to the nearest enclosing pair-like object. This only works with

brackets, though, so arbitrary pairs including quotes are not supported.

The mini.pairs plugin comes with gsf and gsF keybindings, which can be

used to move your cursor to the character in question. I don’t use these,

because the mini.ai plugin provides a similar feature using the g[ and g]

shortcuts. These shortcuts both need to be followed by a character type, so

e.g. g[( will jump back to the nearest surrounding open parenthesis, and

g]] will jump to the nearest closing square bracket. If you give it a count,

it will jump out of that many surrounding pairs.

7.4.5. Highlighting Surrounding Characters

If you just need to double check where the surrounding characters are, you can

use something like gsh(, where h would mean “highlight”. This can

sometimes be used as a dry run for a delete or replace operation that is using

counts so you can double check that you are operating on the pairs you think

you are.

7.4.6. Bonus: XML or HTML Tags

The mini.surround plugin is mostly for working with pairs of characters, but it can also operate on html-like tags.

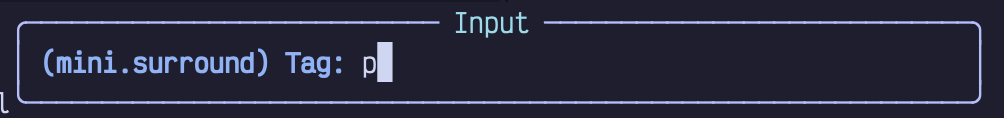

Say you have a block of text and you want to surround it with p tags. String

together the command gsaapt. That is gsa for “add surrounding” followed

by ap for “around paragraph”. So we’re going to add something around a

paragraph. Instead of a quote or bracket, we say the thing we are going to add

is a t for tag.

mini.surround will understand that you want to add a tag, and pop up

a little prompt window to enter the tag you want to add. Type the p

for the tag you want to create. You don’t need angle brackets; just the

tag name:

Figure 30. Surround With Tag

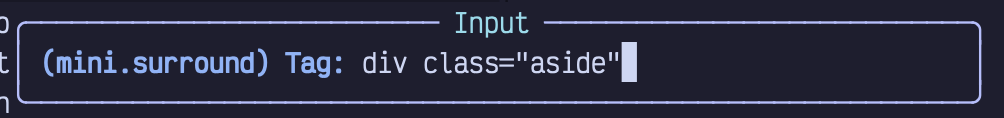

If the tag you want to add has attributes, you can add them to the prompt. mini.surround is smart enough to know that the attributes only go on the opening tag.

Figure 31. Suround Tag Attributes

7.4.7. Modifying the Keybindings

I love the mini.surround behaviour. I use it a lot. So much that I quickly got

tired of typing gs repeatedly. I decided to replace the gs with a ; so I

can instead type ;d or ;r instead of gsd or gsr. For adding surrounds,

I decided to leverage the fact that double keypresses are easy to type, so I

used ;; for that action instead of gsa or even ;a.

In order for this to work correctly, I also had to modify the flash.nvim

configuration to remove the ; command. (By default the ; key can be used as

a “find next” behaviour for the f and t keys, but the way flash is

designed, you don’t need a separate key for it; just press f or t again).

If you want to do the same thing, just create a new Lua file named whatever you

want (mine is extend-mini-surround.lua) inside the config/plugins directory.

The contents of the file will be:

Listing 21. Configuring Mini.surround And Flash

return {

{

"echasnovski/mini.surround",

opts = {

mappings = {

add = ";;",

delete = ";d",

find = ";f",

find_left = ";F",

highlight = ";h",

replace = ";r",

update_n_lines = ";n",

},

},

},

{

"folke/flash.nvim",

opts = {

modes = {

char = {

keys = { "f", "F", "t", "T" },

},

},

},

},

}Since we are modifying two plugins, I put two Lua tables inside a wrapping

Lua table, which Lazy.nvim is smart enough to parse as multiple plugin

definitions. The first passes mappings to the opts that are passed

into mini.surround. These will replace the default keybindings that LazyVim

has defined for that table (the ones that start with gs).

The second definition also passes a custom opts table. It replaces the

default keys, which include ; and , with a new table that only defines f,

F, t, and T.

If I had known that ; was being rebound by flash.nvim, I could have

found this solution by reading the config for flash.nvim on the

LazyVim website and seeing what needed to be

overwritten. However I wasn’t able to figure out where the ; was being

defined, and ended up asking for help on the LazyVim GitHub Discussions. People

are really helpful there, and I encourage you to come say hello if you have any

questions. |

7.5. Summary

In this chapter, we learned a bunch of advanced code motion techniques that LazyVim gives us by its reimplementation of Unimpaired mode. Then we learned what text objects are and took in a crash course on the many, many text objects LazyVim provides.

We then covered the exceptionally useful S motion, which can be used to

pick text objects on the fly, as well as the remote variations of R and r.

We wrapped up by going over several new verbs that can be used to work with surrounding pairs of characters such as parentheses, brackets, and quotes.

In the next chapter, we’ll cover clipboard interactions and registers, as well as an entire new Visual mode that can be used for text selection.